The ideas I will discuss in this essay are the closest I’ve gotten so far to a ‘theory of everything’ - an answer to the question of the meaning of life, the universe and everything, but more so just how to live life with peace and fulfilment. Here we will discuss the problem of attachment, the relevance of spirituality to a good life, and the pursuit of virtue as a true intrinsic goal that is a path towards inner peace. I also make the distinction between intentional and state-based virtues.

In On Happiness, I wrote about how the pursuit of 'intrinsic goals' like personal growth, positive relationships and contribution to a greater purpose were a recipe for happiness. A decade on, my perspective has changed - I believe we should consider these goals to be important symptoms and outward manifestations of a meaningful life. What is then the direct object of our aspirations and actions? I believe it's the pursuit of a virtuous life ± spiritual elements, as a path that is uniquely within reach for everyone.

Take positive relationships. Serious longitudinal studies on lifelong happiness and wellbeing have often emphasised the importance of relationships. So much so that the authors of Harvard Study of Adult Development wrote "Happiness is love. Full stop." But there are numerous barriers to a fantastical utopia where everyone is freely loving, trusting and empathetic with one another. We live in a world where intergenerational trauma is extremely common, where conflict and broader social and economic forces shape our lives, and where many struggle to find acceptance in a community, where many live with intractable mental health problems or feel like round pegs in square holes due to being neurodivergent or otherwise 'different'. The findings of happiness studies can also mislead us into a mindset of thinking we need other people - friends, family, partners to be kind and friendly for us to be happy, which is consistent with an anxious attachment schema. This kind of extrinsic thinking is a serious danger towards inner peace, as we've described for material things, but also towards people and ways of life.

Or take a contribution to a greater purpose. Previously I've associated this precept with the importance of finding meaningful work (familiarise yourself with the concept of ikigai if you haven't already!), but this is really a first world perspective - not a reasonable ask for someone facing economic hardship and threat to life and livelihood. How about someone with a serious disability who is reliant on carers for support?

I faced a fundamental question - does happiness have external prerequisites? Is my counsel a general solution for all of humanity or the privileged few? Do I need the world around me to be a certain way to be happy or can I achieve it within myself?

Thoughts about god and spirituality

Recently, my friend Phil messaged me an article by social scientist Arthur Brooks on 'Jung's Five Pillars of a Good Life', which piqued my interest in this area again (serendipitously on the night before my medical school exams!). I thought it was well written and worth reading in full, but a cursory skim will reveal a lot of familiar ideas:

1. Do not fall prey to seeking pure happiness. Instead, seek lifelong progress toward happierness.

2. Manage as best you can the main sources of misery in your life by attending to your physical and mental health, maintaining employment, and ensuring an adequate income.

3. If you’re earning enough to take care of your principal needs, remember that happiness at work comes not from chasing higher income but from pursuing a sense of accomplishment and service to others.

4. Cultivate deep relationships through marriage, family, and real friendships. Remember that happiness is love.

5. If you have discretionary income left over, use it to invest in your relationships with family and friends.

6. Spend time in nature, surround yourself with beauty that uplifts you, and consume the art and music that nourish your spirit.

7. Find a path of transcendence—one that explains the big picture in life and helps you comprehend suffering and the purpose of your existence.

but there was one element that I didn't include in my original equation: faith (or spirituality and philosophy):

Research clearly backs up Jung’s contention. Religious belief has been noted as strongly predictive of finding meaning in life, and spirituality is positively correlated with better mental health; both faith and spiritual practice seem protective against depression. Secular philosophies can provide this benefit as well. Recent papers on Stoicism, for example, have demonstrated that this ancient way of thinking and acting can yield well-being benefits. Many books have been written on the subject, including the psychotherapist Donald Robertson’s Stoicism and the Art of Happiness.

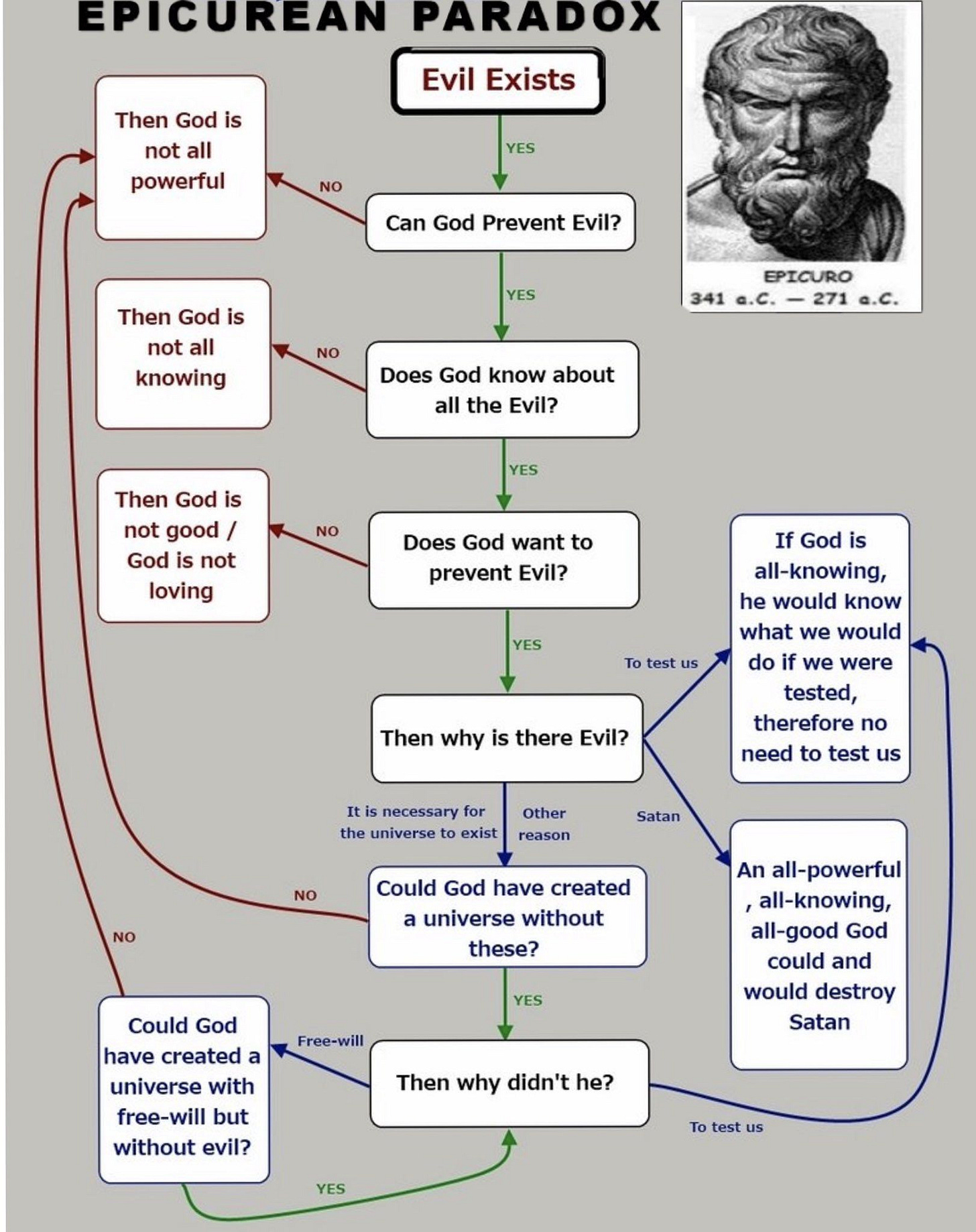

Having grown up alongside my grandmother, who had pretty strong atheist views about religious 'superstitions', my beliefs about spiritual faith have undergone many revisions. As a 5 year old, I remember being shocked that my aunt could believe in god. When I was 11, I remember thinking about the Epicurean paradox, which implies that the there is a logical inconsistency if we claim that god is all good (whatever 'good' means), all-knowing and all-powerful.

and while there are various rebuttals to the problem of evil (e.g. original sin in Abrahamic religions), rigorous lines of enquiry on this and other questions often end up in grey areas of agnosticism ('god works in mystery ways' or 'that's why it's called faith'). I could speak about these issues at length but this would justify an essay for its own sake.

By university, I began to explore spirituality from a different perspective. Several experiences influenced me:

a former maths tutor shared how she was studying in New Zealand under the Colombo Plan scholarship, when the Khmer Rouge took over and killed her family. She spoke of how she leaned into her Buddhist teachings to find peace, compassion and wisdom over suffering. She told me how she learnt to let go of her anger and find acceptance.

some psychedelic experiences showed me how malleable consciousness was - how reality could be experienced on very different terms.

films like Everything Everywhere All At Once and hours meditating in a sauna made me think a lot about everything out there, how vast the universe is, how insane that life and consciousness (things of such complexity and metaphysical properties) emerged at all from entropic randomness. How much of the mysteries of the universe could we ever comprehend in one life time?

I read really interesting perspectives in Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, The Physics of Consciousness: The Quantum Mind and the Meaning of Life by Evan Harris Walker, and short stories like The Egg by Andy Weir that gave me a profound metaphysical and thought-provoking blast about what life could be for.

after joining a local Chinese Christian community in 2022, I began to explore the Christian faith, and was influenced by an educational series that included a lot of personal stories with interesting philosophical nuggets, and felt the visceral power of raw compassion, sacrifice and love in the dramatic portrayals of the Passion of the Christ and The Chosen. I also met many people who shared how they found meaning and support through serious life tribulations through their faith.

I experienced a lot more life and its fair share of emotional hardships - family dysfunction, extreme stress at work, love and loss etc.

I had several conversations about ideas of duty and detachment in Hinduism, exemplified in works such as the Bhagavad Gita (involving Lord Krishna and warrior prince Arjuna).

I meditated in a Zen Buddhist temple in Kyoto Japan, and spoke to the head monk about what he thought enlightenment entailed, though I was not especially impressed by his answer of simply ‘emptying the mind’.

Countless lengthy conversations with older and wiser friends (in their 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s) about their life, their stories and the lessons they took away from it all.

I recently joined a Bahai community after meeting some friends in my medical cohort that were refugees from Iran. I’ve really resonated with their values and beliefs. I might write an explanation of the Bahai faith at some point but if you want to hear some youtube explanations, you can listen to Rainn Wilson (Dwight Schrute from the Office) explain it here or this other guy called Ian. And if you want a taste of the Bahai literature, here is an extract of The Hidden Words. Essentially Bahai’s believe that past religion and spiritual leaders are all ‘manifestations of god’, revealing divine teachings for the particular needs of their age, that most of the world religions have a common message, that god is in many ways unknowable, and that we have an active duty to find unity and peace as part of one human, spiritual family, to break down the barriers of nationhood, race, gender and creed.

I recently met a friend from Iraq who has an incredible personal story and is also of the Islamic faith - I look forward to hearing more.

I learnt a few things from all of this.

(1) spirituality doesn't have to mean religiosity, or following a faith, but rather an openness to the transcendental possibilities of reality as part of a broader ontological enquiry. Moreover, agnosticism and not atheism is the most scientifically coherent position, and spirituality especially when it conveys ideas of love, compassion, self-meditation and accountability etc. can have an extremely positive effect on life meaning. At heart, most people seek or can benefit from moral guidance.

(2) reliance on family, friendships and work is fragile - they are external things that can be taken away. We don't choose family at least half the time, friendships can fracture, people can die or move away, and work isn't always amazing and meaningful, or we may lose the capacity to do the work that we would most enjoy.

Peace is happiness at rest; happiness is peace in motion ~ Naval Ravikant

(3) to have enduring inner peace, one must rest the foundation of that peace on something that is always accessible from within oneself and also inherently meaningful.

The pursuit of virtuous attitudes allows us to navigate the problem of attachment

A very kind and thoughtful man named Neil who has a wealth of life experience spent 3 hours on the phone with me one morning to discuss the ways he faced life’s tribulations. I credit him with really getting me to think about delineating intention and expectation.

The lord giveth and the lord taketh away - Job 1:21

Attachment means we attach our sense of self, our raison d’être, to a thing or person. Attachment and the profound pain arising from loss is universal because it comes so naturally from almost every pursuit of life. From the moment we reach out our tiny little hands as infants, or open our mouths and cry, we begin to desire the possession of things outside of us.

All possession is illusory, and worldly pleasures are evanescent, but attachment goes far beyond material aspirations. We may desire love, but we have no control over the actions or fate of the beloved. We may desire freedom and safety but we may be wrongfully persecuted or incarcerated. We may desire knowledge and learning, but we may suffer a stroke and forget it all.1 We may desire power, but our power is infinitesimal in comparison to the powers of nature. We may desire peace and happiness, but our attachment to it paradoxically bars the way, as we are focused on the possession/attainment of a fleeting state of mind.

The solution to this problem is to turn our efforts towards something where the pursuit (rather than the attainment) of it is intrinsically valuable, meaningful and ‘good’. We call these things virtues.

Specifically I am talking about Virtues of Volition (or intentional/attitudinal virtues) as opposed to Virtues of Attainment (developed capacities). To illustrate the difference, seeking learning and truth is an intentional virtue, but knowledge, an outcome of learning, is a virtue of attainment. Likewise, perseverance is a virtue of volition, but strength and fortitude are attained capacities.

This distinction is important because virtues of attainment are subject to all the shortfalls of possession, whereas virtues of attitude/volition are not. Regardless of our mental or physical circumstance, a virtuous intention is within our grasp.

Another important related idea is that of form versus essence. Essence relates to a truth, whereas form is the way that truth is expressed. For example, one may feel love (an essence), but there are manifold forms to express love, and as external observers we try to identify the essential truth from its outward forms (which is often a cause of misunderstanding). Similarly, ideas are an essence, but language is a form. Sometimes, our construction of language may be so limited that expressing an idea feels like (to borrow a metaphor from Jesus) passing ‘a camel through the eye of a needle’. Even trying to find the right words to describe intentional vs state-based virtues felt like a linguistic challenge - none of the terminology I came up with rolls off the tongue as neatly as I would like.

You whispered softly in the ear of my joyous heart.

You know what's on my mind, you've heard my thoughts.

I closed my mouth and spoke to you in a hundred silent ways.-Rumi

But as you may see, virtues of volition relate to essences, whereas virtues of attainment relate to progress towards forms.

My point here is actually about forgiveness and self-acceptance; while progressive mastery of form is praiseworthy, we should recognise that essence has primacy. Take a poet of one language, and force them to try to speak in another and you will lose the appearance of their eloquence but not the existence of their beautiful thoughts. Likewise we should seek to improve effectiveness of forms but not be too harsh on ourselves if we fall short so long as our essence is pure, that is, pursuing intentional virtues.

But how many of these intentional virtues are there?

Three foundational virtues necessary for a good life

I believe there are three core virtues that form an axiomatic foundation to encompass or derive all the other virtues.

Truthfulness ('the eyes') - the foundation of all virtues, for how can a person progress if they cannot see things clearly? or are not inspired to learn? honesty (know thyself) is a part of this, and so is curiosity and humility.

Love ('the heart') - compassion, generosity, forgiveness, respect, kindness, nurturance. Love when practised well feels beautiful to the giver and beautiful to the receiver. True love is unconditional (unattached). It is inspiring and begets more love. Love is the food of the soul and the wellspring of many pleasures.

Perseverance ('the hands') - all people are subject to mortal limitations. we are limited in mind and body. but perseverance and courage is what allows us to become a force in the world. while our eyes allow us to see the target, and our heart gives us the desire to move towards it, the hands allow us to reach out for it.

Each of these virtues is necessary but not sufficient. Lack of any one of these, and a person is dysfunctional and hollow…

love and courage without truth is foolish and naïve

truth and strength without love is cold, self-interest

truth and love without perseverance is feeble and ineffectual

but together, a person becomes a complete, radiant mirror to the divine - kind, wise and courageous. Can you think of a moral quality that can’t be derived from these three?

Each element of the triad is also interconnected: we derive pleasure (love) from learning and effort; truthfulness and love expresses perseverance (courage, inner strength); love and perseverance requires comprehension etc.

In some cultures like Kazakh or even the fictional Na’vi of James Cameron’s Avatar (2009), the literal phrase ‘I see you’ has a deeper meaning of ‘I love you’ or ‘I respect you’; a profound expression of connection. That is, to see deeply into a person’s self, to see them truthfully, tends to naturally bring forth love. And vice versa, to see someone truthfully you must seek understanding, which is an expression of love.

For this reason I have chosen to represent the three virtues much like a tripartite yin-yang symbol, depicting an element of the other within each virtue. Each is mutually reinforcing of the others, giving rise to more love, joy, and metaphysical meaning.

In other words, wellbeing, happiness, eudaimonia (Aristotle’s term for human flourishing), inner peace etc. arise (as epiphenomena) from the pursuit of intentional virtues, rather than being the direct goals.

They are the fruits of the tree of virtuous life, that may bring forth abundant harvest when the season is right and the tree is vigorous and healthy. But do not dwell on the fruits that have grown, but rather nurture and tend to the tree itself. As any good gardener knows, one should water the roots and not the fruit.

To phrase this less metaphorically…

Meditate each day on whether you have been truthful, loving and persevering. If you have, then it’s a good day. If you haven’t, then that’s why you still exist, to try better. nothing else really matters.

The path of virtue grows the spirit and is the meaning of our existence

Perhaps the words so far are reasons sufficient to pursue a life of virtue. But I will make some further commentary about divine and theological reasons for why we’re here. There are no more axioms upon which to apply logic or empirical observations of the world to justify claims, but merely personal belief and intuition.

We are god’s children, sent here to develop divine attributes through trial and tribulation in a world where we are limited (deprived of godlike capabilities), as power and knowledge in the hands of those without truthfulness, love and perseverance is disastrous. Have gratitude for every moment as each moment is placed for our spiritual growth. Every person we encounter we should treat with compassion because we are all students in the school of life. Some are struggling and no one is there yet, so we should be humble and forgiving. Our existence and the world can be likened to a womb or egg, from which we will be born into the next, once we have become sufficiently practiced in the qualities of the soul.

Or as Abdu’l-Baha put it:

In the beginning of his human life man was embryonic in the world of the matrix (the womb). There he received capacity and endowment for the reality of human existence. The forces and powers necessary for this world were bestowed upon him in that limited condition. In this world he needed eyes; he received them potentially in the other. He needed ears; he obtained them there in readiness and preparation for his new existence. The powers requisite in this world were conferred upon him in the world of the matrix, so that when he entered this realm of real existence he not only possessed all necessary functions and powers but found provision for his material sustenance awaiting him.

Therefore in this world he must prepare himself for the life beyond. That which he needs in the world of the Kingdom (the next world) must be obtained here. Just as he prepared himself in the world of the matrix by acquiring forces necessary in this sphere of existence, so likewise the indispensable forces of the divine existence must be potentially attained in this world. – Abdul-Baha, Foundations of World Unity p. 63.

The seed of virtue is present in all of us, and merely requires nurturance. We must tap into our divine natures to thrive.

All the time too that the child is in the womb of its mother, it receives all its life and nourishment from outside of itself; if it were cut off from that life, it would be in a dead state; so it is with the soul here, if it is cut off from its spiritual food, it is dead. - ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Bahá’í Prayers 9, p. 47-48

Moreover, there is no shortage of problems in our world to practice our virtues on…

Every age hath its own problem, and every soul its particular aspiration. The remedy the world needeth in its present-day afflictions can never be the same as that which a subsequent age may require. Be anxiously concerned with the needs of the age ye live in, and centre your deliberations on its exigencies and requirements.

- Bahá’u’lláh, The Tabernacle of Unity

In other words, we should be persistent in alleviating suffering, achieving justice and doing good for the world because it is an authentic expression of our inner pursuits. Our service to the world is not contingent on how likely we are as individuals to change the macroscopic outcome of worldly affairs, but rather a direct and necessary outpouring of our innermost light.

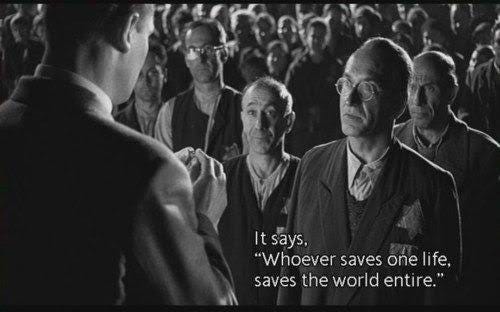

This is why it is written in both the Talmud and the Qur’an that…

Whoever destroys a soul, it is considered as if he destroyed an entire world. And whoever saves a life, it is considered as if he saved an entire world

…because regardless of how what becomes of the world, the practice of good deeds as a manifestation of our inner selves allows our connection to the spiritual world to flourish. And likewise, to neglect the pursuit of virtue is to allow our connection to the spiritual world to decay.

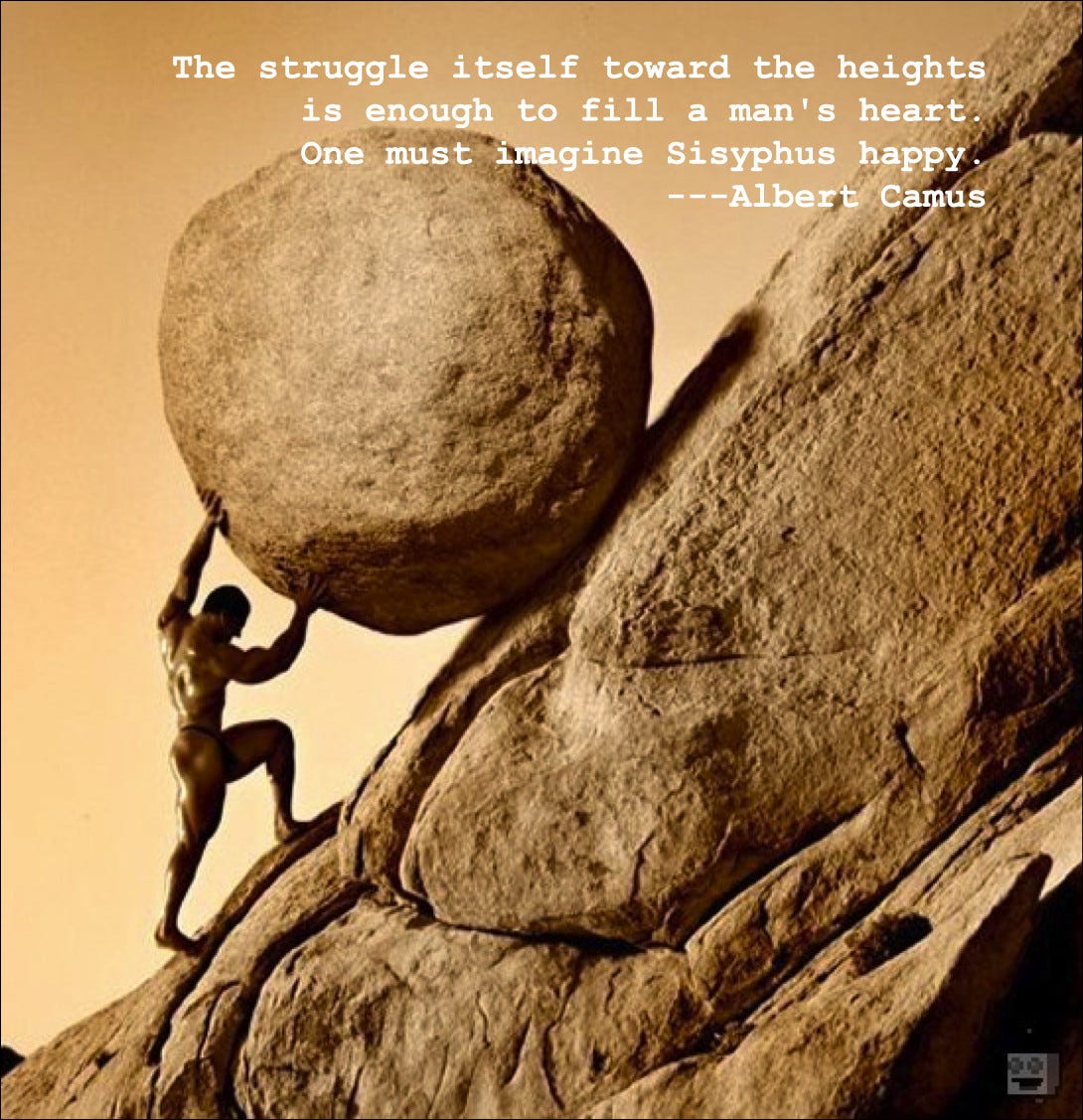

This is the answer to the moral myth of Sisyphus - that however much we embark to help the world, our efforts towards objective improvement may appear to be in vain given so many chaotic forces beyond our control - like the corporate ransacking of the natural world, or political leaders unleashing the destruction of War on the innocent, or the seeming iniquity and hopeless ineptitude of the masses ('L’enfer, c’est les autres!’). But just as it is in our personal lives, the trial and tribulations of our world provide the fertile soil to challenge and spur our collective spiritual growth.

I believe that hidden within the hearts of each of us is the seed of the divine, and an intuitive understanding of what is good. Awakening of this seed and recognition of this shared seed is the foundation of the unification of this world and the realisation of one spiritual family.

Our culture made a virtue of living only as extroverts. We discouraged the inner journey, the quest for a center. So we lost our center and have to find it again.

—Anaïs Nin

An afterthought: An expression of the needs of the collective unconscious?

Carl Jung described the concept of the collective unconscious, a layer of the psyche shared by and shaping all humans, containing universal symbols and patterns, and explaining why myths, dreams and religions across cultures share similar themes.

The second level of the unconscious mind Jung called the “collective unconscious.” According to Jung, the collective unconscious consists of instinctual and universal thought patterns that humans developed over thousands of years of evolution. Jung called these primordial behavior blueprints “archetypes.” For Jung, archetypes form the foundation of all personal experience. It doesn’t matter whether you’re a sophisticated businessman living in a high-rise apartment in Manhattan or a bushman living in a hut in Africa; Jung would argue that no matter who you are, you have the same archetypal behaviors embedded within you.

Jung believed that these archetypes of human behavior came to the surface in the conscious mind through symbols, rituals, and myths. He argued these archetypical patterns explain why we see similar motifs and symbols in rituals and mythical stories across cultures. For example, the dying/resurrecting God figure can be found in the stories and myths of ancient Greeks, ancient Sumerians, Christians, and Native Americans.

~ taken from The Art of Manliness

The collective unconscious contains the whole spiritual heritage of mankind’s evolution, born anew in the brain structure of every individual. ~ Carl Jung

In the book King, Warrior, Magician, Lover: Rediscovering the Archetypes of the Mature Masculine (1990) Jungian psychoanalyst Robert Moore and mythologist Douglas Gillette argue that modern man is often stuck in immature and fragmented expressions of masculinity. This can manifest as brutality and callousness, will to power and manipulation; rejecting of emotions in self and others while hiding shame and fear; dependence and an unhealthy attachment/view to the sensual and the feminine anima. Similar to other Jungian psychoanalysts like James Hollis, they ascribe this to a lack of proper guidance and role modelling in modern culture, in contrast to the sophisticated rites and rituals of many tribal societies that were richly imbued with meaning.

On the other hand, mature masculinity is meant to be generative, creative and empowering for the self and others, but requires the balanced integration of four archetypes of the masculine psyche:

King - representing a central ordering force, including justice and integrity (e.g. Aragorn from LOTR or Atticus Finch from TKMB)

Warrior - representing action and effectiveness (e.g. Maximus Decimus Meridius from Gladiator)

Magician - representing thinking, knowledge, transformation and insight; the archetype of the shaman, scientist or teacher (e.g. Yoda, Alexander Fleming)

Lover - representing feeling, aliveness and connection (e.g. the poet Rumi, [insert your favourite singer], Richard Feynman whom I consider to have one of the greatest stories of love and loss)

While these writers have focussed on the masculine, there are archetypal analogues for the feminine too (Queen/Sovereign, Huntress/Amazon, Mystic/Wise Woman, Lover/Muse, Mother).

I do find it interesting that these mythic archetypes of the collective archetypes correspond very roughly to aspects of the core virtues discussed:

The Magician/Sage represents Truthfulness

The Lover/Parent represents Love

The Warrior represents Perseverance

and from the culmination of all three, arises the King/Queen/Ruler archetype, or the self-actualisation of the self. Realistically however, the archetypes are one or two levels up from the ‘base layer’ of the virtue triad, and thus incorporates more complexity.

“Consider how the human intellect develops and weakens, and may at times come to naught, whereas the soul changeth not. For the mind to manifest itself, the human body must be whole; and a sound mind cannot be but in a sound body, whereas the soul dependeth not upon the body. It is through the power of the soul that the mind comprehendeth, imagineth and exerteth its influence, whilst the soul is a power that is free.” - ‘Abdu’l-Bahá

> 3. If you’re earning enough to take care of your principal needs, remember that happiness at work comes not from chasing higher income but from pursuing a sense of accomplishment and service to others.

Exactly why I quit my job